Between 1159 and 1162, Maestro Guglielmo carved the first monumental marble pulpit for the great Cathedral of Pisa. This work introduced an unprecedentedly extensive and immediately recognisable narrative programme which directly related to the sermons being preached from the pulpit. The cycle included a total of fourteen reliefs illustrating scenes from the Life of Christ including the Annunciation and Visitation and the Three Marys at the Tomb, the Last Supper, the Transfiguration and the Ascension. His design was enormously influential in the region of Tuscany during the mid-twelfth century and first half of the thirteenth century; for example, its classicising, rectangular, two-tier form with groups of protruding full-length figures crowned by an overhanging eagle and angel lecterns, clearly inspired the later pulpit designed by Guido Bigarelli (known as Guido da Como) for the church of San Bartolomeo in Pantano, Pistoia, which was installed between 1239 and 1250. Another sculptor, Fra Guglielmo, carved a pulpit for San Giovanni Fuorcivitas in Pistoia in 1270, which also drew upon the rectangular, double-tiered design of the earlier Maestro Guglielmo.

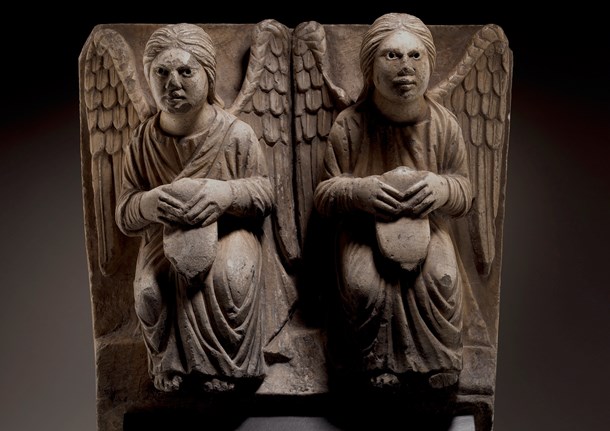

Around 1312 Maestro Guglielmo’s pulpit in Pisa Cathedral was replaced by Nicola Pisano’s polygonal design from 1260 and Maestro Guglielmo’s original was dismantled and sent to Cagliari in Sardinia, to adorn the Cathedral of Santa Maria. Here it was split up to form two pulpits with two lecterns, one representing an eagle and the other a trinity of angels (figs. 3a-b). The angels that appear on one of the pulpits in Sardinia, formerly of Pisa Cathedral, are identical to the present pair, making it highly likely that these also came from the original pulpit at Pisa, but were separated and removed in the process of its dismantling and transportation to Sardinia around 1312.

The primary function of the pulpit in the twelfth-century cathedral was as a platform from which to preach, and the chief role of the present pair of angels upon such a structure would have been to support the heavily bound Gospels and Epistles being read. The style of the present pulpit emerged during the rise of Scholasticism, which was developed in twelfth-century cathedral schools and attempted to synthesise the achievements of Christian and Classical learning. The pulpits represented some of the earliest visual manifestations of the movement, and created a synergy between the verbal and the visual forms of teaching and devotion practiced at the time. For example, whilst Scholastic teaching emphasised preaching in the vernacular tongue, as opposed to Latin, the visual imagery carved on the pulpits from which the sermons were delivered appears markedly more naturalistic, and represents a departure from the abstract forms and symbols of the previous age. In purely artistic terms, the beautifully designed pulpits and lecterns, originating from the mid-twelfth and early thirteen centuries, by the likes of Maestro Guglielmo, Nicola Pisano, Guido Bigarelli (Guido da Como), Fra Guglielmo and their respective circles, represent some of the finest and most important sculptural achievements in pre-Gothic Western art, and they laid the groundwork for the later classicising developments of the Renaissance.